“This collection of poems, from a writer who never saw the Kahiki in person, is a literary Pupu Platter brimming with playfulness, imagination, and reverence.”

Nathalie Wright, Architectural Historian; Columbus, Ohio

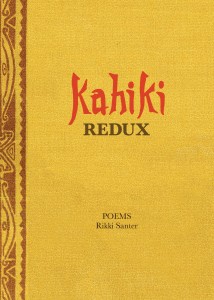

For over forty years, it was the largest freestanding Polynesian restaurant in the country and the site where generations of Columbusites relished Tiki culture. As a local poet and former journalist who relocated to Columbus, I became obsessed with learning about the late great Kahiki Supper Club that was razed over ten years ago after being placed on the National Historic Register. The result of my research and many interviews is Kahiki Redux, a poetry collectionin which I tried to capture the nuances of this pop-culture icon that for decades brought delight and pride to the Columbus cultural landscape. If you’d like to order a copy, please mail a cashier’s check or money order for $20.00 (includes postage) to: 897 Plum Ridge; Columbus, Ohio 43213. Please address the check to Rikki Santer. Thanks for your support. SECOND EDITION JUST PUBLISHED WITH ADDED POEMS.

___________________________________________________________________________

from The Columbus Dispatch; Sunday June 17, 2012

“Poems carry a tiki torch for Kahiki” by columnist Joe Blundo

One of the most grievous crimes ever committed against Columbus architecture was the demolition of the Kahiki in 2000.

The restaurant was shaped like a giant war canoe, had a cultlike corps of devotees and featured flaming drinks, canned thunder and thatched huts. After standing at 3583 E. Broad St. for almost 40 years, it was torn down to make way for a Walgreens pharmacy.

But the memory lives. Its artifacts are auctioned on eBay, and websites recall its splendors. And now a collection of Kahiki poems has been published.

Kahiki Redux by Rikki Santer manages to evoke the appearance and ambience of the place despite the fact that the author has never been inside it.

“. . . At the Outrigger Bar, decked in the robes of our birthdays, anniversaries or lusty prom promises, we suck Pupu Platter goo from our Occidental nails,” she writes in Remembering the Kahiki.

In “Landscape,” she describes carloads of tourists arriving “to lose themselves inside this romantic cocoon that serves up foreign paradise in pineapple carcasses and caricature tumblers.”

Santer, who teaches film studies and English at Upper Arlington High School, moved to central Ohio from Baltimore not long before the Kahiki was demolished. It had already given way to Walgreens when she became interested in it after she and her husband bought a house featuring a Polynesian room.

The room — full of lava rock, tortoiseshell light fixtures and animal-print fabrics — was designed by Coburn Morgan, who was also responsible for the Kahiki’s hyper-Polynesian decor.

Her interest stimulated, Santer began researching the restaurant. She interviewed workers, patrons and the two businessmen who built it: Bill Sapp and Lee Henry. They sold their interests in the restaurant in 1979. (Henry called Santer’s book “terrific.”)

Acknowledging their work is one of the reasons she wrote the book, Santer said.

“My motivation is just to get a memory book into people’s hands. I was so shocked that this icon was torn down. We’re in this bicentennial year, and Bill and Lee are still alive, in their 80s, and they haven’t been recognized formally.”

The book, which is available through Amazon Books or through her website at rikkisanter.com, contains eight poems, Kahiki artwork and a forward by architectural historian Nathalie Wright. She submitted the application that got the restaurant listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1997, a distinction that couldn’t save it.

The last poem, “Kahiki in the Museum,” acknowledges as much, envisioning what would be in a Kahiki historical exhibit: “Lipstick-stained napkins and bite-marked straws from virgin lips; a pyramid of etched glassware; a plastic volcano erupting in gleeful streams of snapshots that incriminate with outdated fashion.”

This might not be the end of Kahiki literature. Santer said she and Wright hope to produce a full-scale history of the place.

Said Santer: “I have great affection for that restaurant.”